Farming

Drawing of a Giant Fennel, The Herbarium of the Manchester Museum

Farming was a traditional way of life for many Romans and country estates were especially important to the Roman aristocracy. Pliny quotes extensively from practical farming manuals written by both Greeks and Romans. He intended his Natural History to be a handy ready reference that would be used by farmers as well as the landed gentry.

Roman farmers tended olive groves and vineyards, grew grain and other crops and grazed livestock. As the empire expanded new kinds of fruit were discovered. Cherry trees were introduced after Roman general Lucullus’ victories in the east during the 1st century BC. The pistachio nut was brought to Italy by Vitellius during the 1st century AD. There were 41 varieties of pear. Roman farmers grafted fruit such as plums onto other trees, although Pliny believed the practice attracted bolts of lightning.

The Silphium

Ancient Greek silver coins of Cyrene in North Africa showing the silphium plant and its seeds.

Silphium became extinct because of over production, disease and changing agricultural practices. The last silphium, a valuable plant used in used in medicine and cooking, was sent as a gift to the emperor Nero (AD 54-68). The leaves of the silphium plant were like parsley and the stalk tasted like fennel. It was similar in appearance to the giant fennel which still grows today.

Bramble Frog

Picture of toad from Robert M.Degraaf The Book of the Toad (The Lutterworth Press, Cambridge,1991).

Being bitten, stung or poisoned must have been a common occurrence in Roman times because Pliny devotes a great deal of the Natural History to remedies of various sorts. Some are related to the bramble frog, which sounds like a creature from Beatrice Potter but must have been some kind of venomous toad. The bramble element of its name presumably comes from the fact that contact with its venomous skin induces a painful skin reaction. Pliny offers a number of remedies for such conditions and also recommends using the bramble frog as a means of combating agricultural pests and calamities and also as a treatment for illnesses:

'Many persons for the more effectual protection of millet, recommend that a bramble frog should be carried at night round the field before the hoeing is done, and then buried in an earthen vessel in the middle. If this is done, they say, neither sparrow nor worms will attack the crop (Book 18, Chap.45).'

Also, 'Archibius has stated in a letter to Antiochus, king of Syria, that if a bramble frog is buried in a new earthen vessel in the middle of a cornfield, there will be no storms to cause injury.' (Book 18, Chap.70 - Remedies Against these Noxious Influences.)

'...frogs boiled in oil on a spot where three roads meet, the flesh is thrown away and the patient rubbed with the decoction as a cure for the quartan fever (malaria)... the best remedy for quartan fevers, is to wear attached to the body either frogs from which the claws have been removed, or else the liver or heart of a bramble-frog, attached in a piece of russet-coloured cloth.' [Book 32, Chap.38 (10)]

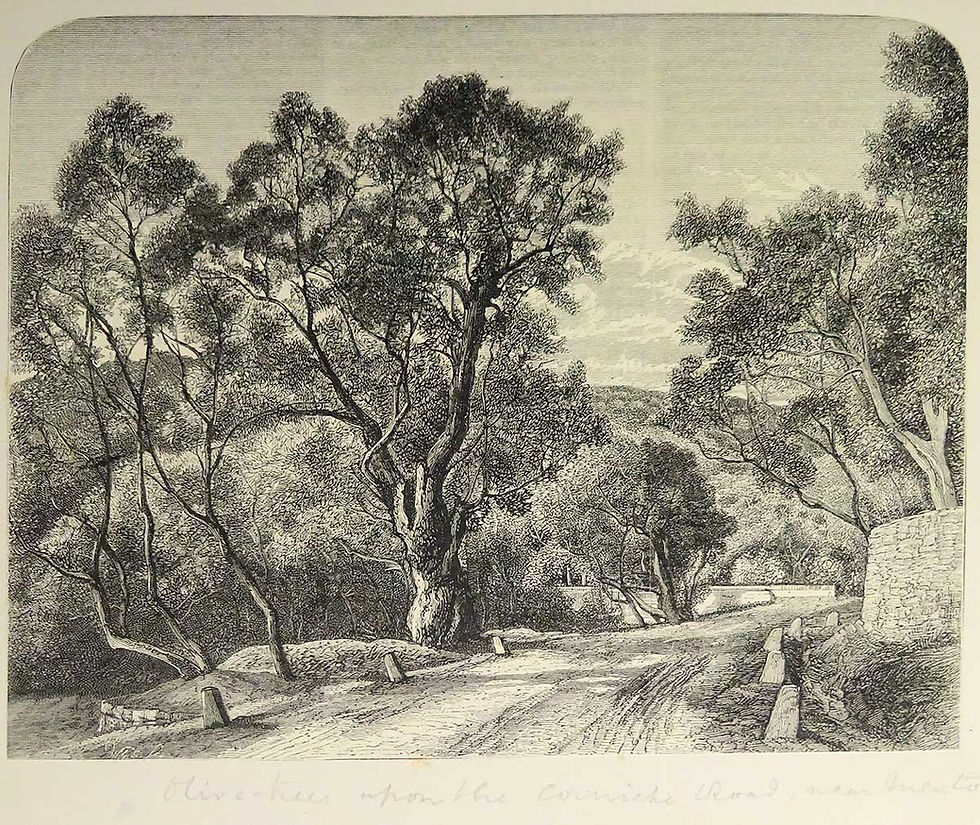

Olives and Pears

Olive tree interview

The oldest olive tree on Crete

Farming Objects

1. Pliny writes that if a farmer carries a bramble frog around a field and buries it in a pot before working the soil it will prevent sparrows and worms from eating the crop. Roman pot from London.

2. Silphium was a commercially important plant used in medicine and cooking that grew in North Africa. Ancient Greek coins show it was similar to the giant fennel which still grows today except that is seeds were heart-shaped. It became extinct because of over production, disease and changing agricultural practices. The last silphium was sent as a gift to the emperor Nero (AD 54-68).

3. Roman lamps showing locusts. Locusts sometimes destroyed crops in Italy.

4. Roman lamp from Italy showing a sheep. Late 1st century AD.

5. Piece of olive wood and picture of ripe olives from the Museum Herbarium. Olive trees were extremely useful and provided olives for eating and pressing to make into oil.

6. Roof tile with animal paw print. The number of prints on tiles suggests animals were constantly wandering about. From the civilian settlement, Malton Roman fort. Loan from Malton Museum.

7. Roman samian ware bowl from Manchester showing vine tendrils and artificial grapes. Pliny wrote that ‘wine refreshes the stomach, sharpens the appetite, takes off the keen edge of sorrows and anxieties, warms the body, acts beneficially as a diuretic and invites sleep.’

8. Lead cockerel, lamp and spurs from the legs of fighting birds. The cockerel was a farm bird but it was also used for fighting and bets were placed on the outcome.

9. Hazelnuts and walnuts from the bottom of the well at Langton Roman Villa, near Malton, North Yorkshire. Pliny tells us that shells of the green walnut were used in dyeing. Loan from Malton Museum.

10. Burnt grain from Malton Roman fort. Grain infested by pests was often burnt. Loan from Malton Museum.